The History of First Water Car, The crime scene is in Grove City, Ohio, Franklin County.With all the ingredients of the setting in the American province that is dear to crime writers. It’s the 21st March 1998, the first day of spring, and four men are having lunch in a restaurant. A waiter serves one of them some cranberry juice, perhaps (but we will never know for sure) chosen for dessert. This man, immediately after the first sip, suddenly gets up as if he’s gone crazy, he holds his hands around his neck, he loses his breath, runs out into the parking lot, collapses to the ground and pronounces his last words “they poisoned me”.

Steve Robinette, the lead detective on the case, collected the testimonies of everyone in the parking lot, including the final disturbing words of a man immediately identified as Stanley Meyer, a citizen of Grove City. His brother Stephen was one of the four at the table, and he heard the words spoken at the end of his life. Robinette is not one for interminable investigations. He performed a toxicology analysis, which gave no significant results, and he also spoke to the coroner, who attributed his death to a brain aneurysm, compatible with previous episodes of hypertension. In just three months, he closed the case file, sealed it with a coloured elastic band and wrote on the cover “death by natural causes”. Formally, the case was now resolved.

In 2015 Robinette retired from the police force, and devoted himself to politics, becoming president of the city council, and in 2019 he also ran for mayor.

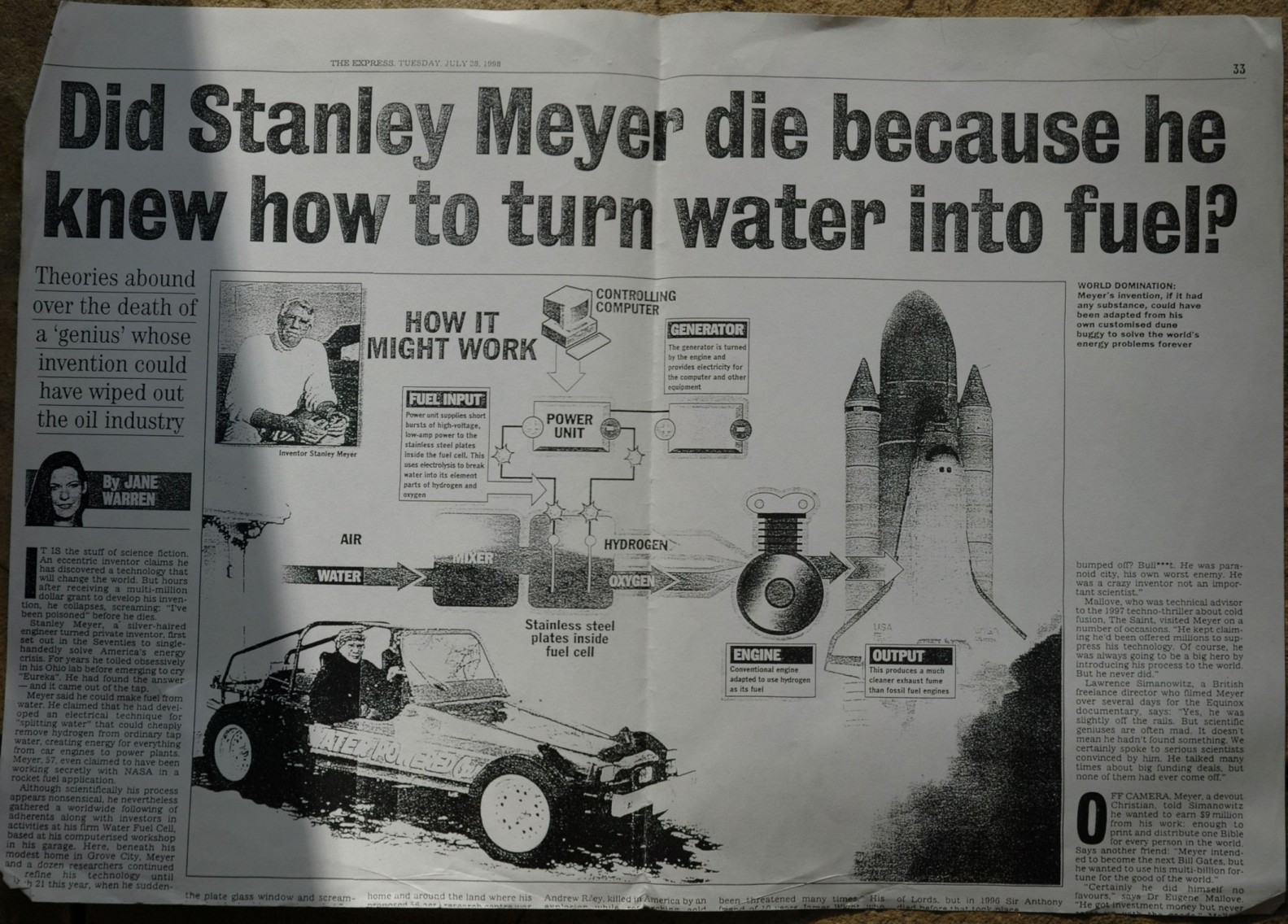

But we can all rest assured that in all these years he never forgot the case of Stanley Meyer, the inventor of the water-powered car who, in 1998, got up from a table at a restaurant to run into a car park, some say just to leave us a message: “they poisoned me, and it’s because of what I’m doing to revolutionize the car world”. The coroner’s report contained the following statement: “no poison known to American science has been found”. But maybe the search for Meyer’s enemies should have gone beyond American soil. We have to go back to 1975, when Meyer, who spent his life patenting technical solutions of every kind, from the banking sector to, ironically, heart monitoring, decided to explore the automotive world. In that year, the effects of the Middle East oil embargo, which had also led to a crisis in the United States, were still considerable, with a significant drop in car sales.

Meyer thought that the way to get out of oil dependency was through water propulsion. Yes, water. A “very” alternative solution, it goes without saying.

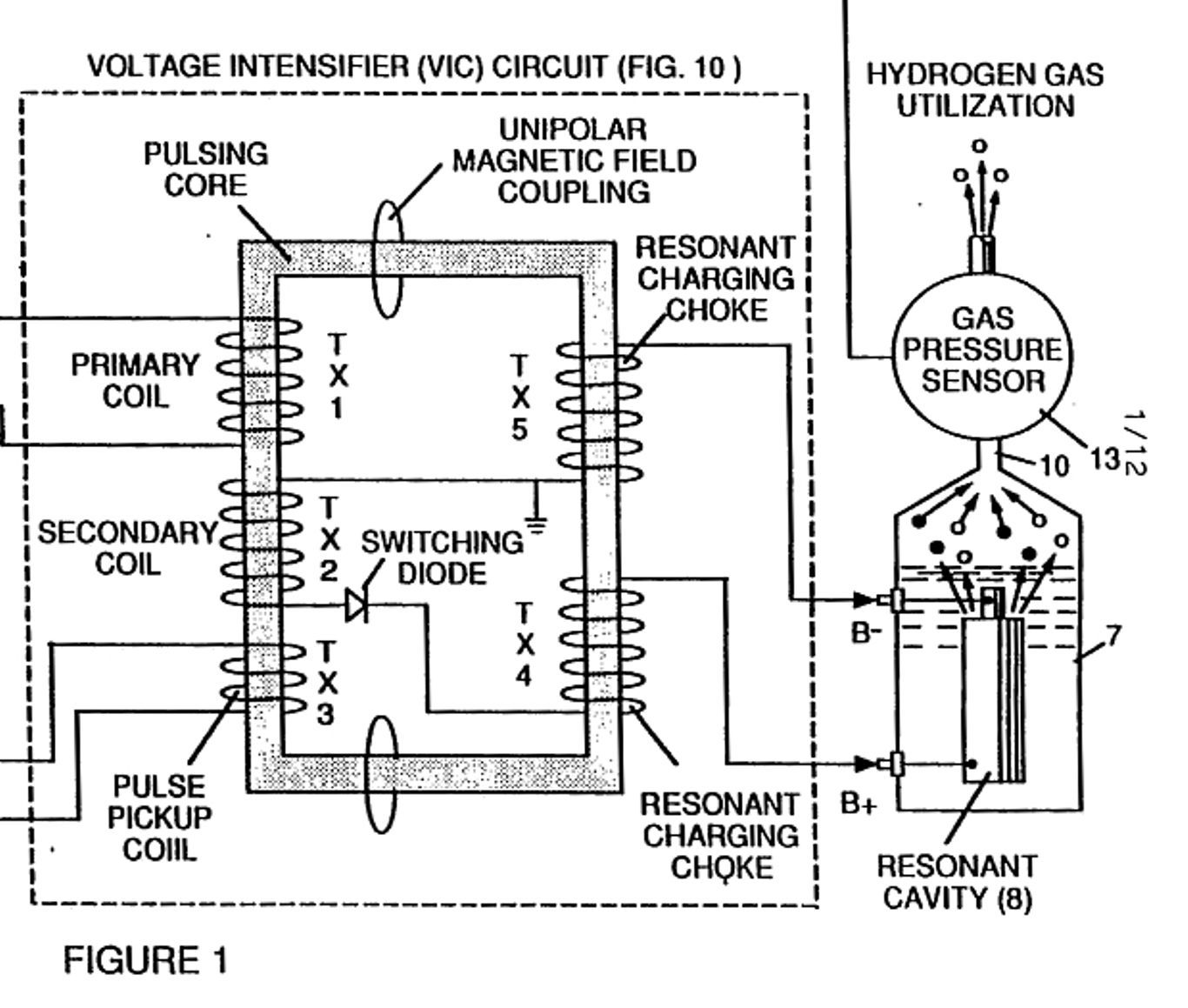

He created a fuel cell, based on the principle of splitting water atoms into its elemental form, burning hydrogen to create energy and releasing oxygen, along with water residues, through the exhaust pipe, thus generating harmless emissions.

After a few months he managed to develop his water-powered engine, mounting it onto a dune buggy painted with the conspicuous writing: “water powered car”, and with a call to his Christian faith, to communicate the spirit of protection and creation, which animated his actions.

Meyer claimed his vehicle was able to travel 180 km. With just 4 litres of water, and nothing else. Forty-five kilometres with just a litre of something that cost hardly anything must have sounded truly magical. And that’s exactly when his troubles started.

Taking a look at what’s left of this inexplicable series of events, there is a film of this moving car, and various photos of the car surrounded by admiring people. But many argue that no one had ever really verified the actual operation of the engine, whether it was powered purely by water and whether the patent or the project worked at all. Analysing the case, there have been rivers of words and ink spent over the years both to support and to refute Meyer’s thesis, and especially the veracity of what he claimed. Even an American judicial authority, in 1996, two years before his mysterious death, had looked into Meyer’s invention, petitioned by several small investors who had financed the development of his project, who later became suspicious and worried that it was doomed to bankruptcy.

The Fayette County Judge (Ohio) had appointed three surveyors, to whom Meyer refused to submit the car, and who concluded by noting that the chemical and technological process “invented” by Meyer would not be at all revolutionary, even going so far as to call it trivial, and that no evidence was provided that it could actually effectively power an automobile engine.

The Judge then issued his verdict, in which he decreed that the funds received by Meyer had been stolen by deception (“gross and egregious fraud”), and he was sentenced to return it to investors. For a man whose livelihood depended on his ingenuity, this was certainly not a small financial pill to swallow and, perhaps worse still, honour. Certainly, this was a very sad epilogue for someone who had proclaimed themselves to be the saviour of the complex equation between efficient automotive propulsion, respect for the environment, and affordable power.

Stanley had previously stated that he had been threatened many times by representatives from oil companies from around the world.

Including tales of car chases with armed guards. Fantasy?

He also claimed he had been offered the hyperbolic sum of a million dollars (some even say a billion dollars) to kill all evidence of his technology, and that he had refused.

A scientist who tried to get in touch with Meyer to learn more about his project declared that Stanley had a “paranoid” attitude, and that he had flatly refused to subject the Dune Buggy to a test in order to verify its performance, even if they promised not to open the “black box” containing the electronic components that powered the system.

We know just how many car manufacturers have faced the delicate problem of hydrogen propulsion – water still lies at the heart of the process – but with far greater design and construction complexities. Stanley and his brother Stephen, despite their defeat, tried to protect what they continued to declare as the invention of the century.

Stephen Meyer claimed that one week after Stanley’s death, unidentified people had stolen the Dune Buggy from Stanley’s garage, along with all of the inventor’s instruments, and that the vehicle had subsequently been found, but it is unclear under what circumstances and conditions.

The patent had been registered, and the Dune Buggy was later closed off in a room without doors, so that no one could steal it and destroy it (but according to Meyer’s detractors, so that no one could examine it and discover the weakness of the patent). It seems that in 2014, and therefore some sixteen years after the death of Stanley, the vehicle turned up in Canada (perhaps sold by his brother Stephen), now under ownership of the Holbrook family (claimed to be old associates of Stanley), but nothing is known of it after that date.

We cannot therefore exclude the possibility of new chapters being added to this thriller, in which reality, reticence and supposition alternate continuously, firmly keeping the suspicion of Meyer’s supporters alive, who still doubt, against all investigative evidence, the purity of that cranberry juice.