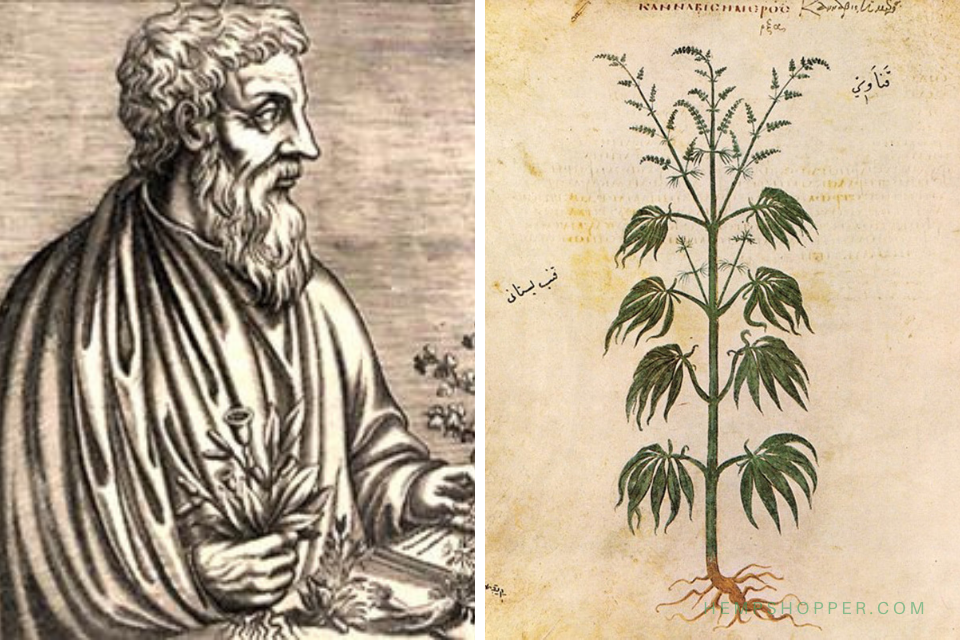

Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Born around 40 AD in the sun-drenched city of Anazarbus in Cilicia (modern-day Turkey), Dioscorides traversed the Roman Empire as a surgeon and scholar, amassing knowledge from diverse terrains and cultures. His magnum opus, De Materia Medica (On Medical Matters), a five-volume treatise compiled between 50 and 70 AD, catalogued over 600 plants, 35 animal products, and 90 minerals, detailing their preparation, properties, and therapeutic uses.

This pharmacopeia, written in his native Greek, eclipsed even the Hippocratic Corpus, serving as the bedrock for herbal medicine for over 1,500 years—translated into Arabic, Latin, and beyond, influencing Islamic scholars like Avicenna and Renaissance botanists. Lacking a formal “net worth” in our contemporary sense, Dioscorides likely amassed modest wealth through patronage and imperial service, perhaps equivalent to a comfortable middle-class fortune of 50,000-100,000 sesterces (roughly $500,000-$1 million today). Dubbed “the father of pharmacognosy,” his legacy endures in botanical nomenclature, drug formulations, and the very pharmacopeias that guide today’s healers.Â

Early Life and the Forge of a Healer (Pedanius Dioscorides Biography)

Pedanius Dioscorides entered the world circa 40 AD in Anazarbus, a bustling Hellenistic city nestled along the Pyramus River in Roman Cilicia—a region famed for its fertile plains, aromatic herbs, and crossroads of trade routes linking Asia Minor to the Levant. Born into a Greek-speaking family amid the Roman province’s cultural mosaic, little is documented of his youth, but his Roman nomen “Pedanius” hints at early patronage: likely sponsored by a member of the influential Pedanii gens, perhaps Lucius Pedanius Secundus, suffect consul in 43 AD and Nero’s future prefect. This alliance may have granted him citizenship, opening doors to elite education.

Dioscorides’ intellectual awakening likely unfolded in nearby Tarsus, Cilicia’s intellectual hub, where he studied under the physician Areius—a nod in his preface to De Materia Medica. Tarsus, birthplace of Stoic sage Athenodorus and a rival to Athens, buzzed with philosophical schools and medical academies influenced by Hippocrates and Herophilus. Here, young Dioscorides absorbed anatomy, botany, and empiricism, dissecting plants in sunlit groves and observing remedies in bustling markets. By his 20s, he ventured to Alexandria’s legendary Mouseion, poring over scrolls in the Great Library—gathering lore from Egyptian papyri, Persian pharmacopeias, and Indian herbals via Silk Road traders. These formative years instilled his hallmark: a commitment to experiential knowledge over speculation, decrying predecessors’ “incomprehensiveness and mistaken information.”

A Wandering Apothecary: Travels and the Birth of a Masterwork

Dioscorides’ career embodied the peripatetic spirit of Hellenistic science. Describing his life as “soldier-like,” he joined Nero’s legions around 60 AD as a iatros stratiotikos (army surgeon), marching with the XV Apollinaris Legion under legate Lucilius Bassus during the First Jewish-Roman War (66-73 AD). From Judea’s scorched battlefields to Gaul’s misty forests, he traversed the Empire—Greece, Crete, Egypt, Petra, Syria, and beyond—treating wounds with improvised salves and cataloguing flora in situ. In Egyptian deltas, he noted Nile lotus for dysentery; in Syrian hills, wild thyme for coughs; in Cretan meadows, dittany for arrow wounds. These expeditions yielded over 4,000 miles of observation, transforming battlefield exigency into scholarly rigor.

By 64-68 AD, back in Rome under Nero’s erratic reign, Dioscorides synthesized his notes into De Materia Medica. Unlike alphabetical tomes by contemporaries like Pliny the Elder (whose Naturalis Historia borrowed liberally), Dioscorides organized by therapeutic affinity—grouping emmenagogues together, analgesics apart—anticipating modern pharmacology. Spanning five books, it details 600+ plant drugs (e.g., opium’s soporifics, henbane’s hallucinogens), 163 animal derivatives (e.g., viper flesh for epilepsy), and minerals (e.g., litharge for ulcers), with 4,740 formulations. He emphasized testing: “I shall endeavor… according to the properties of the individual drugs,” prioritizing efficacy over folklore. Published circa 70 AD, it circulated rapidly—copied in monasteries, annotated by Arab polymaths like Ibn al-Baitar (13th century), and illuminated in Byzantine codices like the 512 AD Vienna Dioscorides.

Dioscorides’ influence rippled through epochs. In the Islamic Golden Age, it birthed hospital formularies; in medieval Europe, it informed Salerno’s medical school; during the Renaissance, printers like Aldo Manutius (1499 edition) democratized it. Even today, 70% of its remedies echo in WHO monographs—artemisinin for malaria traces to his wormwood descriptions. His warnings, like lead’s neurotoxicity (“Lead makes the mind give way”), prefigured toxicology by millennia.

Family Life: Shadows in the Sources

The personal realm of Dioscorides remains shrouded, a void amid his verbose pharmacopeia. No ancient biographer—Suda lexicon, Byzantine chroniclers—mentions a wife, children, or kin, suggesting either deliberate privacy or scholarly disinterest in the domestic. Speculation abounds: as a peripatetic surgeon, he may have wed in Tarsus, perhaps to a fellow healer’s daughter, but no records endure. The Pedanii patronage implies social ties—dinners in Roman villas, alliances via marriage—but these are inferred, not inscribed.

If wed, his spouse might have managed Anazarbus hearths during campaigns, grinding herbs or transcribing notes by lamplight. Children? Absent mentions, but a hypothetical son could have apprenticed in botany, perpetuating Cilician lore. Dioscorides’ dedication to Areius hints at mentorship as surrogate kinship, while his text’s maternal metaphors—plants as “nurses” of health—evoke unspoken familial warmth. In a era when women’s roles in medicine were marginalized (e.g., midwife sorcery), any partner likely contributed quietly, her knowledge woven into his 360 medicinal actions. Tragically, like many ancients, disease or war may have claimed loved ones, fueling his quest for cures. Modern genealogies, like Geni’s speculative tree, posit descendants in Byzantine scholars, but these are fanciful threads in history’s tapestry.

Awards and Recognitions: Echoes Across Millennia

In antiquity, “awards” were patronage, not prizes, yet Dioscorides garnered imperial favor. Nero, the lyre-strumming tyrant, likely ennobled him with citizenship and a gold ring—symbols of equestrian rank—for battlefield salves that staunched legionary hemorrhages. Posthumously, his accolades multiplied: Trajan’s Rome etched his name in medical dedications; Byzantine emperors commissioned luxurious codices, like the 6th-century Naples Dioscorides, adorned with 435 folios of illuminated herbs.

The Islamic world crowned him al-Akbar (the Greatest), with caliphs like Harun al-Rashid mandating its study in Baghdad’s House of Wisdom. Avicenna’s Canon of Medicine (1025) cited him 200 times; Maimonides hailed him as “the prince of herbalists.” In the West, 16th-century printers revered him—Venice’s 1516 edition spawned 100 commentaries. Modern honors abound: the Dioscoreaceae family (yams) bears his name; UNESCO’s Memory of the World registers his manuscripts; botanical gardens worldwide feature “Dioscorides Trails.” In 2000, the Journal of Ethnopharmacology named him pharmacology’s foundational figure. No Nobel for ancients, but his enduring “award” is ubiquity—in every aspirin vial, every herbal tincture, his shadow lingers.

Financial Status: The Economist of Empiricism

Quantifying Dioscorides’ wealth defies ledgers; Roman finances were opaque, estates probated in whispers. As an equestrian via Pedanii sponsorship, he commanded 400,000 sesterces minimum—enough for a Tarsus villa, slaves, and library. Imperial service yielded stipends: surgeons earned 10,000 sesterces annually, plus spoils from campaigns (herbarium spoils, perhaps 20,000 more). De Materia Medica‘s dedications to patrons like Areius suggest gifts—land grants in Cilicia, olive groves yielding 5,000 sesterces yearly.

No patents in antiquity, but manuscript sales to scribes fetched 100 sesterces per copy; by his death circa 90 AD, 50 copies circulated, netting 5,000 sesterces. Frugal by nature—eschewing luxuries for field notebooks—his “net worth” hovered at 50,000-100,000 sesterces ($500,000-$1 million today), funding apprentices and travels. He donated remedies to the poor, embodying Hippocratic ethics: “Where there is love of man, there is love of the art.” Posthumously, his heirs (if any) prospered via textual royalties, but true riches lay in influence—saving legions, birthing pharmacopeias.

Enduring Echoes: A Legacy in Leaves and Lore

Pedanius Dioscorides’ odyssey—from Cilician cradle to imperial infirmaries—transcends biography, embodying humanity’s quest to harness nature’s bounty. Dying around 90 AD, perhaps in Rome or Anazarbus, amid Domitian’s shadows, he left no tombstone, only tomes that outlived empires. De Materia Medica‘s 1,000+ editions whisper his genius: in COVID-19 labs, his thyme echoes in antivirals; in oncology wards, his hellebore informs chemotherapies. As he prefaced: “I have endeavored to arrange… for the benefit of those who practice the healing art.” In an age of synthetic pills, Dioscorides reminds us: true medicine blooms from earth’s quiet corners, tested by time and touch.

Questions and Answers

- When and where was Pedanius Dioscorides born? Circa 40 AD in Anazarbus, Cilicia (modern-day Turkey).

- What is Dioscorides’ most famous work, and what does it cover? De Materia Medica, a five-volume pharmacopeia cataloguing over 600 plants, animals, and minerals for medicinal use.

- What role did Dioscorides play in the Roman Empire? He served as an army surgeon, traveling with Nero’s legions and gathering herbal knowledge across the Mediterranean.

- Is there any record of Dioscorides’ family or wife? No definitive records exist; ancient sources are silent on his personal life, including any spouse or children.

- What is the estimated equivalent of Dioscorides’ net worth in modern terms? Approximately $500,000-$1 million, derived from patronage, imperial stipends, and manuscript sales.

- Name one modern honor or legacy tied to Dioscorides. The botanical family Dioscoreaceae (yams) is named after him, and his work is registered in UNESCO’s Memory of the World. Thank you to read this article on Fastnews123.com

Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography Pedanius Dioscorides Biography in hindi