History of First Computer, The first modern electronic digital computer was called the AtanasoffâBerry computer, or ABC. It was built by physics Professor John Vincent Atanasoff and his graduate student, Clifford Berry, in 1942 at Iowa State College, now known as Iowa State University. Thatâs where I have been teaching computer engineering for over 30 years, and Iâm also a collector of old computers. I got to meet Atanasoff when he visited Iowa State and got a signed copy of his book. Before ABC, there were mechanical computing devices that could perform simple calculations. The first mechanical computer, The Babbage Difference Engine, was designed by Charles Babbage in 1822. The ABC was the basis for the modern computer we all use today.

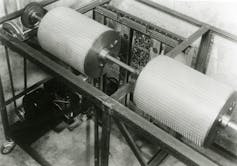

The ABCâs drums.

Courtesy of Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives, CC BY-ND

The ABC weighed over 700 pounds and used vacuum tubes. It had a rotating drum, a little bigger than a paint can, that had small capacitors on it. A capacitor is device that can store an electric charge, like a battery.

The ABC was designed to solve problems with up to 29 different variables. You might be familiar with equations with one variable, like 2y = 14. Now imagine 29 different variables. These are common problems in physics and other sciences, but were difficult and time-consuming to solve by hand.

Atanasoff was credited with several breakthrough ideas that are still present in modern computers. The most important idea was using binary digits, just ones and zeroes, to represent all numbers and data. This allowed the calculations to be performed using electronics.

Another idea was the separation of the program (the computer instructions) and memory (places to store numbers).

The ABC completed one operation about every 15 seconds. Compared to the millions of operations per second of todayâs computer, that probably seems very slow.

Unlike todayâs computers, the ABC did not have a changeable stored program. This meant the program was fixed and designed to do a single task. This also meant that, to solve these problems, an operator had to write down the intermediate answer and then feed that back into the ABC. Atanasoff left Iowa State before he perfected a storage method that would have eliminated the need for the operator to reenter the intermediate results.

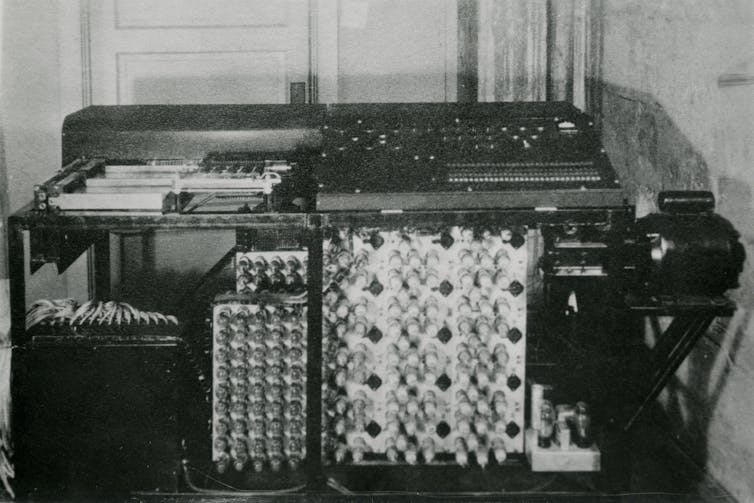

Part of the ABC.

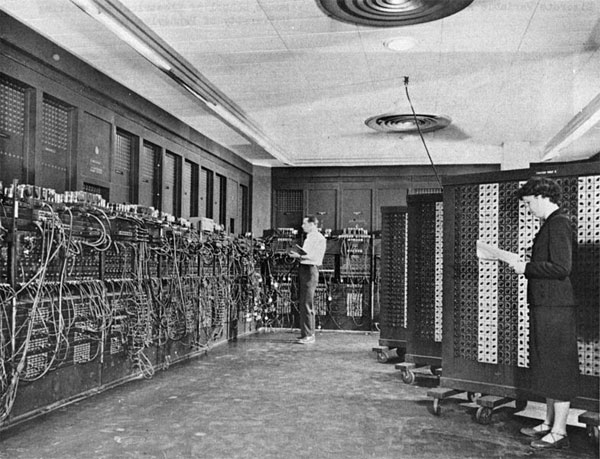

Courtesy of Iowa State University Library Special Collections and University Archives, CC BY-NDShortly after Atanasoff left Iowa State, the ABC was dismantled. Atanasoff never filed a patent for his invention. That means that, for a long time, many people werenât aware of the ABC. In 1947, the creators of the Electronic Numerical Integrator And Computer, or ENIAC, filed a patent. This allowed them to claim they were the inventors of the digital computer. For several decades, most people thought that the ENIAC was the first modern computer. But one of the inventors of the ENIAC had visited Atanasoff in 1941. The courts later ruled that this visit influenced the design of the ENIAC. The ENIAC patent was thrown out by a judge in 1973.The holders of the ENIAC patent argued that the ABC never really worked. Since all that remained was one of the drum memory units, it was hard to prove otherwise. In 1997 a team of faculty, researchers and students at Iowa State University finished building a replica of the ABC. They were able to demonstrate that the ABC did function. You can see the replica today at the Computer History Museum in Mountain View, California.

Computers and electronics play an enormous role in today’s society, impacting everything from communication and medicine to science. Although computers are typically viewed as a modern invention involving electronics, computing predates the use of electrical devices. The ancient abacus was perhaps the first digital computing device. Analog computing dates back several millennia as primitive computing devices were used as early as the ancient Greeks and Romans, the most known complex of which being the Antikythera mechanism. Later devices such as the castle clock (1206), slide rule (c. 1624) and Babbage’s Difference Engine (1822) are other examples of early mechanical analog computers.

The introduction of electric power in the 19th century led to the rise of electrical and hybrid electro-mechanical devices to carry out both digital (Hollerith punch-card machine) and analog (Bushâs differential analyzer) calculation. Telephone switching came to be based on this technology, which led to the development of machines that we would recognize as early computers.

The presentation of the Edison Effect in 1885 provided the theoretical background for electronic devices. Originally in the form of vacuum tubes, electronic components were rapidly integrated into electric devices, revolutionizing radio and later television. It was in computers however, where the full impact of electronics was felt. Analog computers used to calculate ballistics were crucial to the outcome of World War II, and the Colossus and the ENIAC, the two earliest electronic digital computers, were developed during the war.

With the invention of solid-state electronics, the transistor and ultimately the integrated circuit, computers would become much smaller and eventually affordable for the average consumer. Today âcomputersâ are present in nearly every aspect of everyday life, from watches to automobiles.

Charles Babbage, an English mechanical engineer and polymath, originated the concept of a programmable computer. Considered the “father of the computer”, he conceptualized and invented the first mechanical computer in the early 19th century. After working on his revolutionary difference engine, designed to aid in navigational calculations, in 1833 he realized that a much more general design, an Analytical Engine, was possible. The input of programs and data was to be provided to the machine via punched cards, a method being used at the time to direct mechanical looms such as the Jacquard loom. For output, the machine would have a printer, a curve plotter and a bell. The machine would also be able to punch numbers onto cards to be read in later. The Engine incorporated an arithmetic logic unit, control flow in the form of conditional branching and loops, and integrated memory, making it the first design for a general-purpose computer that could be described in modern terms as Turing-complete.

The machine was about a century ahead of its time. All the parts for his machine had to be made by hand â this was a major problem for a device with thousands of parts. Eventually, the project was dissolved with the decision of the British Government to cease funding. Babbage’s failure to complete the analytical engine can be chiefly attributed to political and financial difficulties as well as his desire to develop an increasingly sophisticated computer and to move ahead faster than anyone else could follow. Nevertheless, his son, Henry Babbage, completed a simplified version of the analytical engine’s computing unit (the mill) in 1888. He gave a successful demonstration of its use in computing tables in 1906.